January 26, 2009--The dark disk of the moon creeps across the setting sun during the first solar eclipse of 2009, as seen on Monday from Manila Bay in the Philippines.

People viewing from the southern Indian Ocean were among the few to see the full annular eclipse, so called because at its peak the eclipse is surrounded by an annulus, or ring, of fiery light.

Because the moon's orbit is elliptical, its distance from Earth--and thus its apparent size--varies over time. Annular eclipses happen when the moon looks too small to completely cover the sun, an event that occurs about 66 times a century.

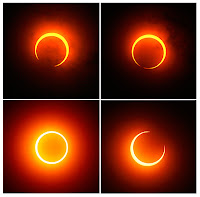

A sequence of photos shows the moon passing between Earth and the sun before, during, and after an annular eclipse, as seen on January 26, 2009, from Bandar Lampung in Indonesia.

A sequence of photos shows the moon passing between Earth and the sun before, during, and after an annular eclipse, as seen on January 26, 2009, from Bandar Lampung in Indonesia.

The path of the full annular eclipse crossed mostly open ocean in the southern part of the globe, starting about 560 miles (900 kilometers) south of Africa and not reaching land until it crossed Australia's Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean.

Still, observers in southern Africa, Madagascar, Australia, and Southeast Asia were able to watch a partial eclipse. Astronomer Jay Pasachoff used a specially equipped camera to capture images of the January 26, 2009, annular eclipse from the Indonesian island of Java.

Astronomer Jay Pasachoff used a specially equipped camera to capture images of the January 26, 2009, annular eclipse from the Indonesian island of Java.

Pasachoff, chair of the International Astronomical Union's working group on eclipses, has received funding from the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration to study the sun during the total solar eclipse on July 22, 2009. (The National Geographic Society owns National Geographic News.)

snow fall

World Clock

ENDLESS TIME

THe Endless World Link

Emily Sohn, Discovery News

Jan. 21, 2009 -- By the end of the century, the hottest temperatures in recent history will become typical, and the world's food supply will be in deep trouble as a result.

Those grim predictions come from a new study that looked at heat waves of the past as well as climate projections for the future to paint a frightening picture of what's to come: severe food shortages and rising malnutrition, especially in places where people are already poor and hungry.

"The changes are so big and in the wrong direction in places where it really matters," said agricultural economist David Bittisti, of the University of Washington, Seattle. He led the study, which appeared recently in the journal Science.

Battisti urges immediate reductions in fossil fuel emissions and agricultural preparations for a warmer world.

"If we don't adapt, we will have really serious problems," he told Discovery News. "People will need to either migrate or die."

Battisti and colleagues used 23 global climate models to forecast average growing season temperatures through the end of the century. All the models agreed: With our current rate of greenhouse gas emissions, there is a greater than 90 percent chance that by 2100, summers in the tropics and subtropics will be hotter than the hottest summers recorded between 1900 and 2006.

Associated Press

Jan. 15, 2009 -- The ocean's delicate acid balance may be getting help from an unexpected source, fish poop.

The increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere not only drives global warming, but also raises the amount of CO2 dissolved in ocean water, tending to make it more acid, potentially a threat to sea life.

Alkaline chemicals like calcium carbonate can help balance this acid. Scientists had thought the main source for this balancing chemical was the shells of marine plankton, but they were puzzled by the higher-than-expected amounts of carbonate in the top levels of the water.

Now researchers led by Rod W. Wilson of the University of Exeter in England report in the journal Science that marine fish contribute between 3 percent and 15 percent of total carbonate.

And the contribution may be even higher than that, say the researchers from the U.S., Canada and England.

They report that bony fish, a group that includes 90 percent of marine species, produce carbonate to dispose of the excess calcium they ingest in seawater. This forms into calcium carbonate crystals in the gut and the fish then simply excrete these "gut rocks."

The process is separate from digestion and production of feces, according to the researchers.

The team estimated the total mass of bony fish in the ocean at between 812 million tons and 2,050 million tons, which they said could produce around 110 million tons of calcium carbonate per year.

The carbonate produced by fish is soluble and dissolves in the upper sea water, while that from the plankton sinks to the bottom, the team noted.

The research was funded by the U.K. Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, The Royal Society, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, United Nations Environmental Program, the Pew Charitable Trust and the U.K. Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

AFP

Jan. 13, 2009 -- The Earth's climate has been significantly affected by the planet's magnetic field, according to a Danish study published Monday that is unlikely to challenge the notion that human emissions are largely responsible for global warming.

"Our results show a strong correlation between the strength of the Earth's magnetic field and the amount of precipitation in the tropics," one of the two Danish geophysicists behind the study, Mads Faurschou Knudsen of the geology department at Aarhus University in western Denmark, told the Videnskab journal.

He and his colleague Peter Riisager, of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS), compared a reconstruction of the prehistoric magnetic field 5,000 years ago based on data drawn from stalagmites and stalactites found in China and Oman.

The results of the study, which has also been published in scientific journal Geology, lend support to a controversial theory published a decade ago by Danish astrophysicist Henrik Svensmark, who claimed the climate was highly influenced by galactic cosmic ray (GCR) particles penetrating the Earth's atmosphere.

Svensmark's theory, which pitted him against today's mainstream theorists who claim carbon dioxide (CO2) is responsible for global warming, involved a link between the earth's magnetic field and climate, since that field helps regulate the number of GCR particles that reach the earth's atmosphere.

"The only way we can explain the (geomagnetic-climate) connection is through the exact same physical mechanisms that were present in Henrik Svensmark's theory," Knudsen said.

"If changes in the magnetic field, which occur independently of the Earth's climate, can be linked to changes in precipitation, then it can only be explained through the magnetic field's blocking of the cosmetic rays," he said.

The two scientists acknowledged that CO2 plays an important role in the changing climate, "but the climate is an incredibly complex system, and it is unlikely we have a full overview over which factors play a part and how important each is in a given circumstance," Riisager told Videnskab.

John Flesher, Associated Press

Jan. 8, 2009 -- Dozens of foreign species could spread across the Great Lakes in coming years despite policies designed to keep them out, causing significant environmental and economic damage, a federal report says.

The National Center for Environmental Assessment issued the warning in a study released this week. It identified 30 nonnative species that pose a medium or high risk of reaching the lakes and 28 others that already have a foothold and could disperse widely.

Among the fish that scientists fear could cause ecological and environmental damage are the monkey goby, the blueback herring and the tench, also known as the "doctor fish."

The report described some of the region's busiest ports as strong potential targets for invaders, including Toledo, Ohio; Gary, Ind.; Duluth, Minn.; Superior, Wis.; Chicago and Milwaukee.

"These findings support the need for detection and monitoring efforts at those ports believed to be at greatest risk," the report said.

Exotic species are one of the biggest ecological threats to the nation's largest surface freshwater system. At least 185 are known to have a presence in the Great Lakes, although the report says just 13 have done extensive harm to the aquatic environment and the regional economy.

Perhaps the most notorious are the fish-killing sea lamprey and the zebra mussel, which has clogged intake pipes of power plants, industrial facilities and public water systems, forcing them to spend hundreds of millions on cleanup and repairs.

Roughly two-thirds of the new arrivals since 1960 are believed to have hitched a ride to the lakes inside ballast tanks of cargo ships from overseas ports.

For nearly two decades, U.S. and Canadian agencies have required oceangoing freighters to exchange their fresh ballast water with salty ocean water before entering the Great Lakes system. Both nations also recently have ordered them to rinse empty tanks with seawater in hopes of killing organisms lurking in residual pools on the bottom.

Despite such measures, "it is likely that nonindigenous species will continue to arrive in the Great Lakes," said the report by the national center, which is part of the Environmental Protection Agency.

Some saltwater-tolerant species may survive ballast water exchange and tank flushing, it said. And aquatic invaders could find other pathways to the lakes -- perhaps escaping from fish farms or being released from aquariums.

The report does not predict which species might get through. Instead, it urges government resource managers to monitor waters under their jurisdiction in hopes of spotting attacks in time to choke them off.

"Early detection is crucial," said Vic Serveiss, a scientist with the National Center for Environmental Assessment and the report's primary writer.

Hugh MacIsaac, a University of Windsor biologist and director of the Canadian Aquatic Invasive Species Network, said he expected very few invaders to reach the Great Lakes in ballast water now that both nations are requiring tank flushing at sea. Flushing and ballast water exchange should kill 99 percent of organisms, he said.

"I would be very surprised if their prediction comes true," he said, referring to the EPA report's suggestion that numerous invaders could reach the lakes despite the new ballast rules.

The report reinforces the need for further measures to keep foreign species out, including requiring onboard technology to sterilize ballast tanks, said Jennifer Nalbone, invasive species director for the advocacy group Great Lakes United.

"We are only beginning to invest the tremendous amount of resources needed," Nalbone said. "We're being hammered by invasive species and are still woefully behind."